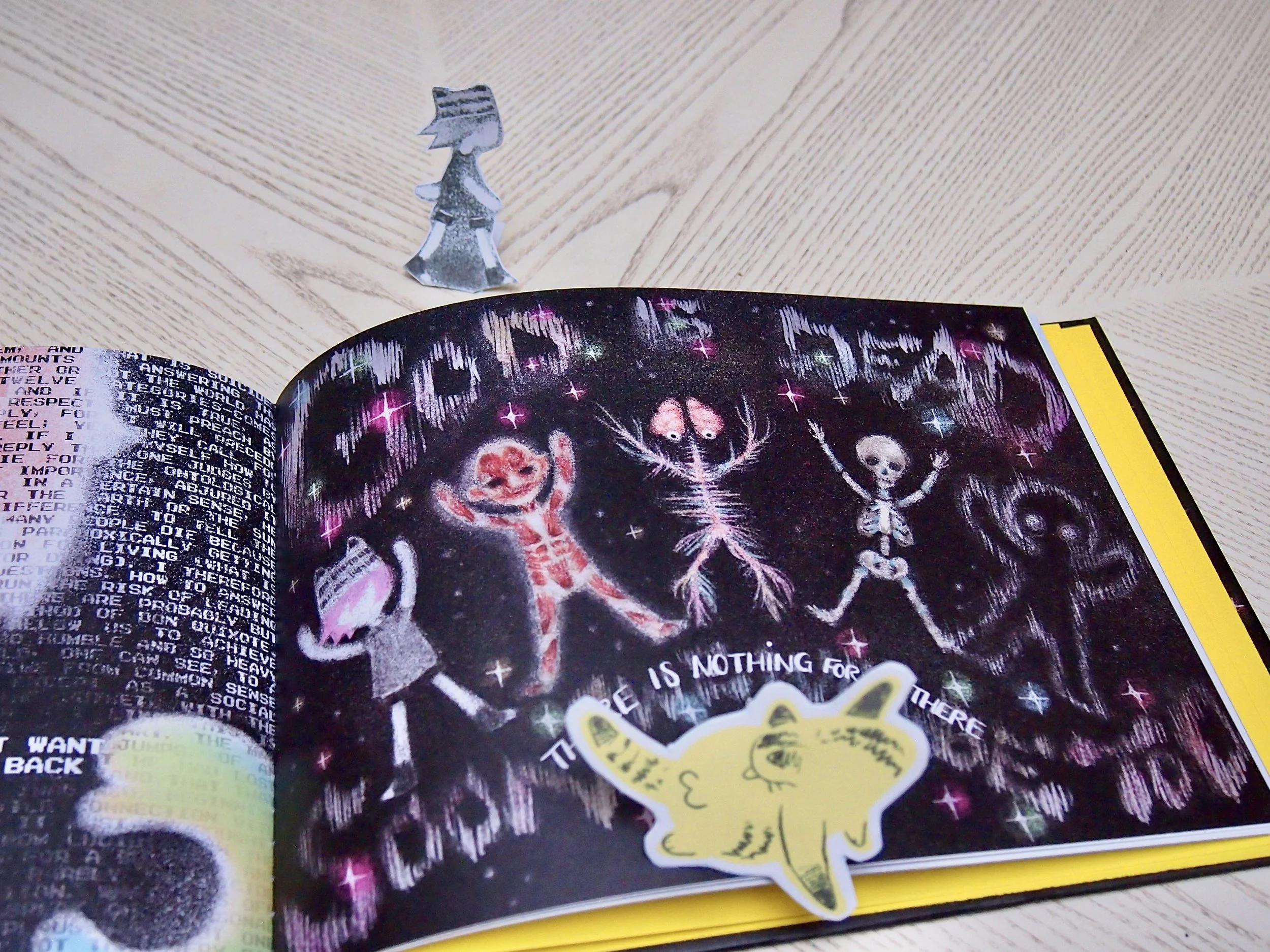

What is the point of life? If there is no God, no ultimate purpose, no soul and no resolution, what do we live for? We are thrust into the world against our will, uttering our first cry at the pain of being ripped away from blissful non-existence. We spend our existence struggling for meaning; directionless in life. Whilst at the same time we are faced with the unchangeable, terrifying fate of our own mortality; as if being driven off a cliff tied to the passenger seat, incapable of changing the result yet forced to live through the experience. Pushing a boulder uphill only for it to fall back down again, and again, and again. In the existential sense, life must be torture.

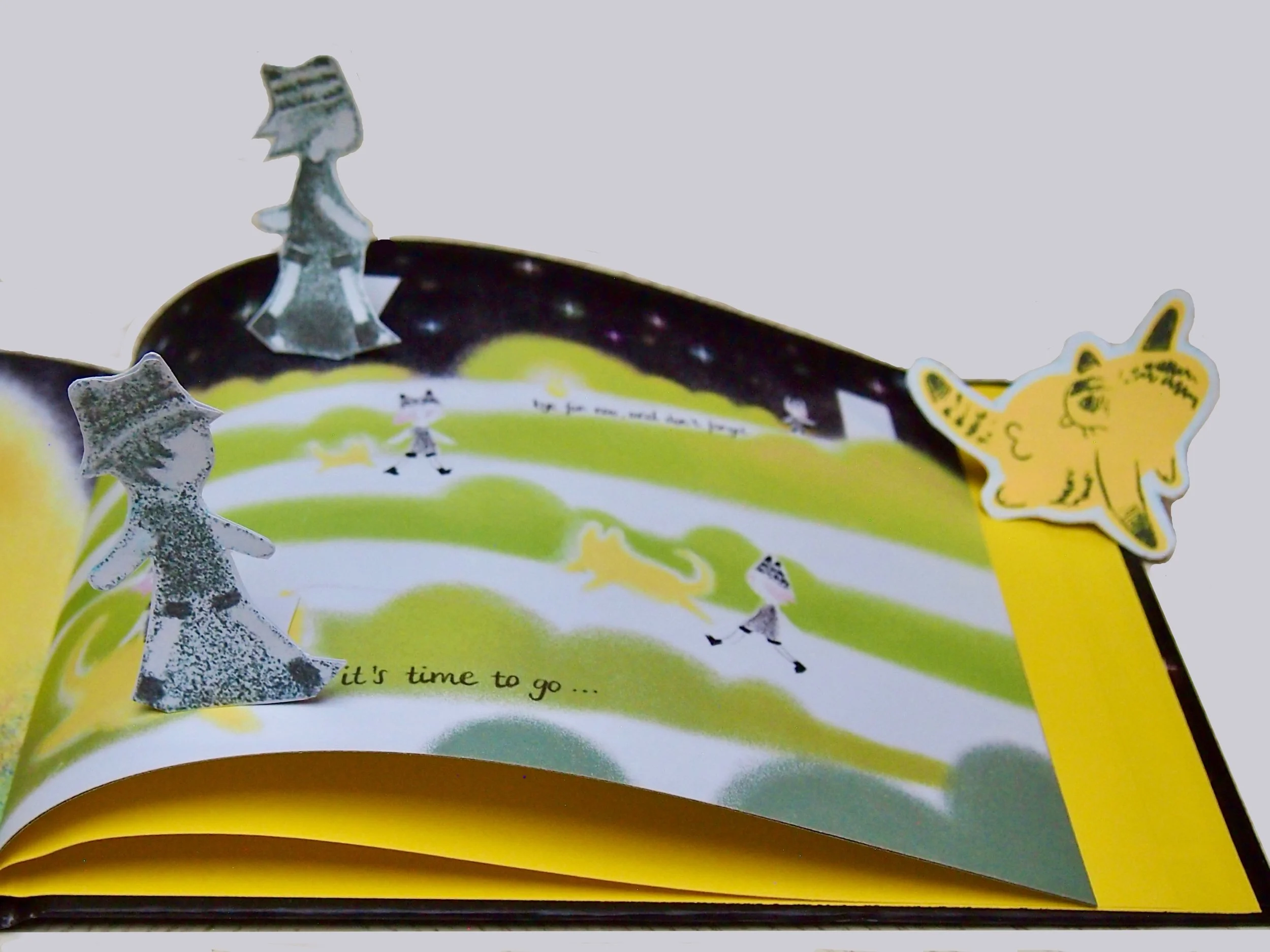

If existence is so absurd, how can we justify life? If we live in absence of God, of ideology, of any meaning at all, how can we bear to suffer our own existence? Gabriel Marcel’s answer is to counter the “call of the void” with “presence”, “communion” and “hope”. Presence: openness to others. Communion: exploration of the self through sharing with another. This hope is not optimism; not blind belief that everything will be well, but instead strength and courage to face life in spite of despair. Hope marks the distinction between problem and mystery. For the problematic man, life is a series of problems which require solutions. Whereas to be truly hopeful, one must come to terms with the mystery of life. Existence is an experience, a philosophical mystery to engage with rather than a problem to be solved. Perhaps the point of living is just to live. Perhaps one must imagine Sisyphus happy.

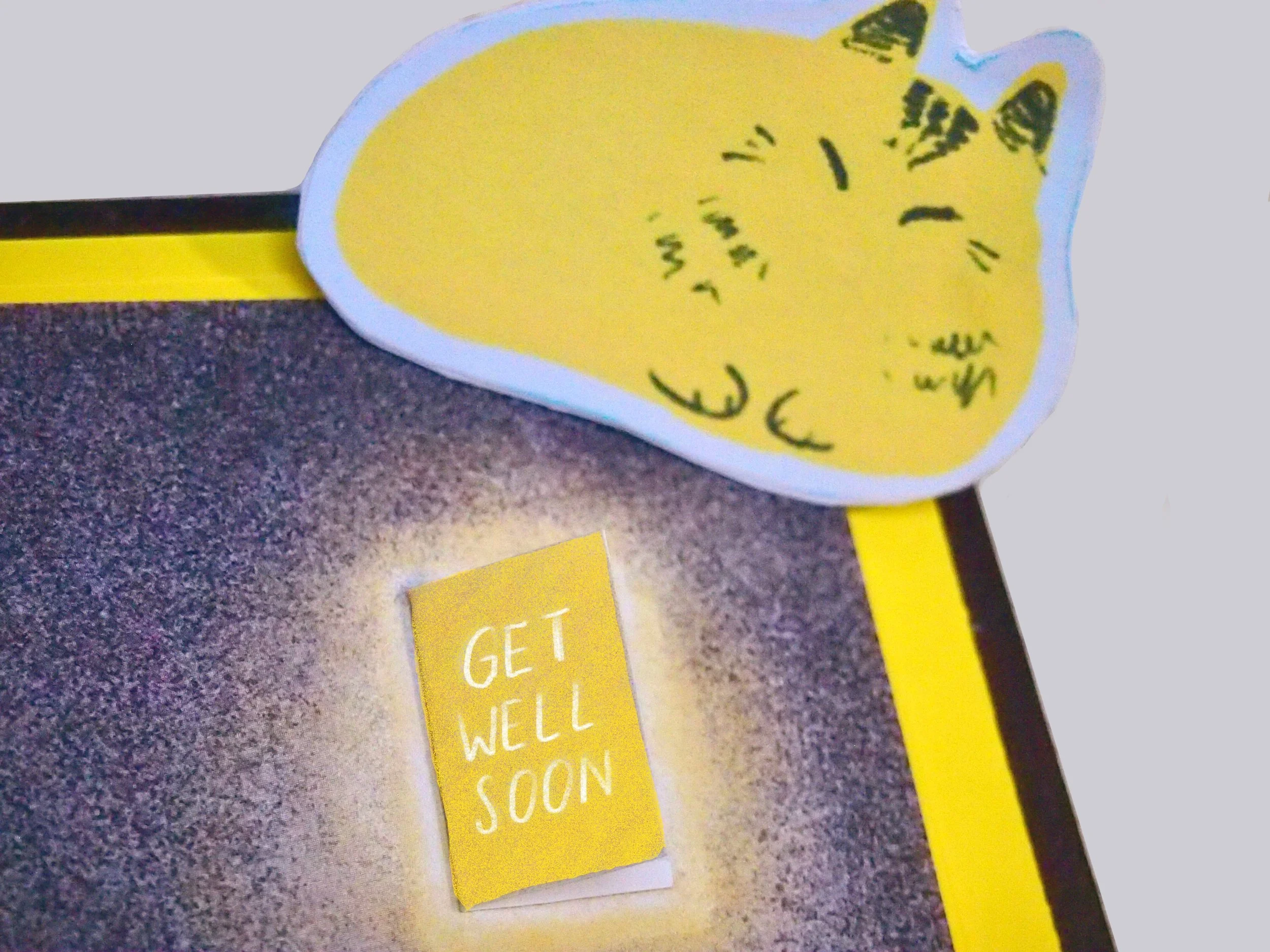

One Ninth addresses this exact theme of combatting nihilism. At the start, our protagonist is laden down by the seeming futility of life, feeling as if everyday is a monotonous dawdle. Through a journey of discovery, she comes to learn to appreciate the little things in life and begins to start embracing life by the end of the book.